history

First Typewriters

In 1714, British engineer Henry Mill was granted the first known patent (No. 376) for a “Machine for Transcribing Letters” onto paper with the appearance of print. Although no design details are known, his wording clearly anticipates the concept of the typewriter and is widely regarded as the earliest description of such a device.

‘An artificial machine or method for the impressing one after another, as in writing, whereby all writings whatsoever may be engrossed in paper or parchment so neat and exact as not to be distinguished from print.’

His machine was apparently never made.

Around 1808, Italian inventor Pellegrino Turri built the first documented typewriter. He created the machine for his blind friend, Countess Carolina Fantoni da Fivizzano, enabling her to correspond with him after she moved to another city. Several of her letters still exist and are the earliest known examples of typed correspondence.

The first American typewriter patent was granted to William Austin Burt of Michigan in 1829 for a machine he called the Typographer. It did not feature a keyboard but used a lever mechanism to select characters. Constructed primarily of wood, the device was about the size and shape of a bread box. Though never commercially produced, it drew some favorable attention in the New York Commercial Advertiser, which described it as “a simple, cheap, and pretty machine for printing letters, should it be found to fully answer the description given of it.”

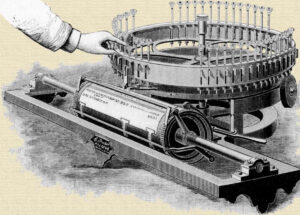

In 1843, Charles Thurber of Massachusetts was granted a patent for a machine he called the Patent Printer. It featured a large rotating horizontal wheel with a plunger for each character arranged around its perimeter. Beneath the wheel was the first cylindrical platen – or roller – used on a typing machine. This roller moved laterally to feed the paper and introduced a design that would become standard in all future typewriters.

In 1853, John Jones of New York introduced a machine he called the Mechanical Typographer. An illustrated advertisement for the device proudly proclaimed: “For Printing Letters, Poetry, Cards, Contracts, Lessons, Compositions, Notes etc. as fast as the majority of people can write with a Pen.”

The typewriter did go into production, with approximately 130 units manufactured before a fire destroyed the entire factory. Only two examples are known to survive: Jones’s original prototype, now in the Dietz Collection at the Milwaukee Public Museum, and another in a private collection.

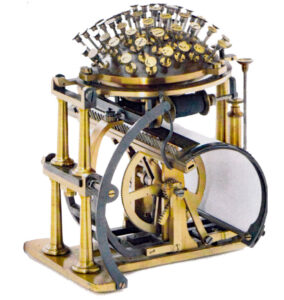

In 1870, Danish clergyman Rasmus Malling-Hansen invented a machine he called the Writing Ball. With its dome-like shape covered in type plungers, it resembled something from a mad scientist’s laboratory. Designed primarily for blind typists to produce text readable by the sighted, the machine was both innovative and visually striking. Several versions were manufactured, with around 500 units produced. Despite this modest success, the Writing Ball was not the breakthrough that would secure the typewriter’s place among the century’s most transformative inventions. That role would fall to the Sholes and Glidden, introduced in 1874 – though even it saw only limited success until the mid-1890s, when the typewriter finally gained widespread acceptance.

The standard big black typewriters we recognize today were the result of decades of mechanical evolution throughout the 19th century. In the early years, between 1800

The standard big black typewriters we recognize today were the result of decades of mechanical evolution throughout the 19th century. In the early years, between 1800 and 1870, around forty inventors attempted to create a practical writing machine. However, none of their designs were produced in significant numbers, nor did they succeed in capturing the world’s imagination.

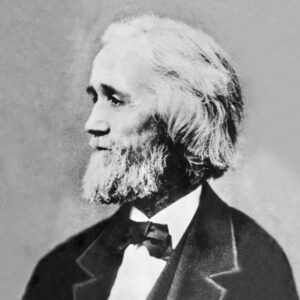

In Milwaukee in 1866, inside the bustling Kleinstuber’s Machine Shop, Christopher Latham Sholes began developing a typewriter with the help of a small team of machinists and financial backers. Over the next six years, they built fifty prototypes, eventually producing a workable machine made largely of wood. Though delicate and often requiring adjustments to function properly, they managed to sell about one hundred units locally. Despite their efforts, a dozen companies rejected the idea of manufacturing the device, and a growing sense of discouragement – especially felt by Sholes – began to set in. It seemed unlikely their machine would ever reach large-scale production.

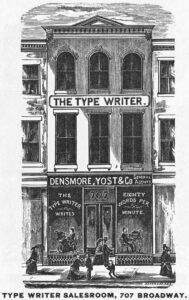

That changed in 1873, when backers James Densmore and George Yost presented the newly named Type Writer to Remington & Sons of Ilion, New York. The timing was ideal: with the Civil War over and a declining demand for firearms, Remington was actively seeking new commercial ventures. Known for their precision engineering and capacity for mass production, Remington was uniquely positioned to take on the project.

After the demonstration, Philo Remington turned to company executive Mr. Benedict and asked, “What do you think of it?” Benedict replied, “That machine is very crude, but there is an idea there that will revolutionize business.” When Remington asked, “Do you think we ought to take it up?” Benedict responded, “We must on no account let it get away. It isn’t necessary to tell these people that we are crazy over the invention, but I’m afraid I am pretty nearly so.” A tentative agreement was reached that day.

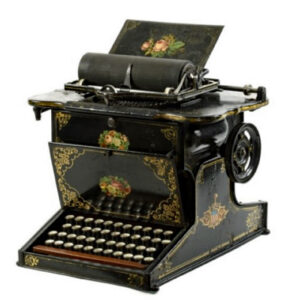

Remington assigned two of their top machinists to transform the wooden prototype into a refined metal machine, complete with hand-painted floral decorations and pastoral scenes. By 1874, the first of 4,000 Sholes & Glidden Type Writers rolled out of the factory – marking the beginning of the modern typewriter era.

Sholes and Glidden typewriter

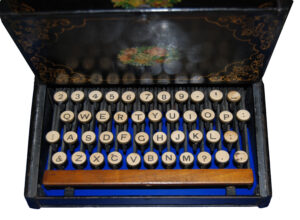

The Sholes and Glidden typewriter of 1874 was the first to introduce the QWERTY keyboard layout. This arrangement was designed to prevent the type bars from clashing by separating letters that are often typed in sequence, such as ‘t’ and ‘h’.

Later, more efficient keyboard layouts were proposed once typewriter designs had evolved and jamming was less of a problem. However, by then, people had already learned the QWERTY arrangement and understandably were reluctant to switch.

Interestingly, the word ‘typewriter’ can be typed using only the top row of the QWERTY keyboard. It is said this was intentional, allowing salesmen to quickly type the word ‘typewriter’ to impress curious onlookers. This is likely true, as the odds of those letters appearing randomly in the same row are very low.

The Sholes and Glidden keyboard included only uppercase characters. Its successor, the Remington 2 typewriter of 1878, featured a shifting carriage that allowed both upper and lower case characters.

The social custom of handwritten correspondence was firmly rooted in the Victorian age. Early typed letters, breaking with this tradition, were generally met with resistance.

J.P. Johns, a Texas insurance man and banker who purchased a Remington typewriter in the late 1870s, received this tepid response from one of his insurance agents:

“I received your communication and will act accordingly. There is a matter I would like to speak to you about. I realize, Mr. Johns, that I do not have the education which you have. However, until your last letter, I have always been able to read your handwriting. I do not think it was necessary then, nor will it be in the future, to have your letters taken to the printers and set up like a handbill. I will be able to read your writing and am deeply chagrined to think you thought such a course necessary.”

As the years passed and rapid business growth strained existing office capacities, managers became more willing to embrace labor-saving practices and let old etiquette slip away. The typewriter’s extraordinary advantages — speed, legibility, and the ability to produce multiple copies at once – could not be ignored.

Being first is not always easy. The Sholes & Glidden typewriter sold very slowly in its first two years, and even after that only achieved moderate success. New technology in any era takes time to be recognized and understood, and, as is often the case, even the inventors may not fully grasp the true value of their own creation.

Here are the main reasons for the very slow early sales of the typewriter:

High Price

The Sholes & Glidden sold for $125—a considerable amount at the time. A horse-drawn carriage cost between $30 and $75, and an upright piano could be purchased for $100.

Misguided Marketing

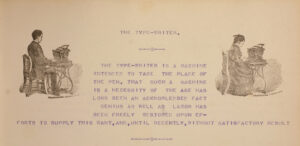

Surprisingly, the typewriter was not initially marketed for the general business office. Instead, it was promoted as a labor-saving device for “ministers, lawyers, authors, stenographers, and all who desire to escape the drudgery of the pen.”

Cultural Resistance

Handwritten correspondence was the social convention in the Victorian age, and the shift to typed letters was often seen as impersonal or inappropriate, breaking with established etiquette.

Lack of Skilled Typists

There were very few trained typists at the time to take full advantage of the machine’s speed and efficiency.

A Menagerie of typewriters

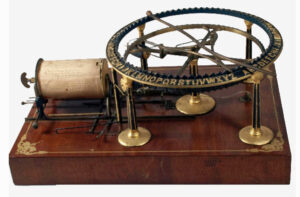

The ‘index’ class of typewriter is defined by the absence of a keyboard. Instead, a dial, knob, or lever is used to select the characters to be printed.

It may seem odd that index typewriters were made at a time when keyboard machines were already available – especially since typing was slower on an index machine – but they were far less expensive. Index typewriters sold for $5 to $40, while keyboard machines ranged from $60 to $100. In the 1880s and 1890s, this was a significant difference, especially when compared to a clerk’s weekly wage of $5, a horse-drawn carriage costing $40–70, or a piano at $65.

For those with poor handwriting, speed wasn’t the only advantage. The ability to produce legible writing made the index typewriter especially attractive. These machines found popularity in small businesses and homes throughout the 1880s and 1890s, with many remarkable designs emerging. However, as secondhand keyboard machines became more widely available, and the benefits of touch-typing became clear, the market for index typewriters quickly faded by the turn of the century.

Many examples of these ingenious index typewriters can be seen in this collection.

Twentieth-century typewriters all look and work much the same: four straight rows of keys, a single shift key, and a front-strike visible typebar mechanism, where you can see what you type as you type it.

But imagine you had never seen a typewriter and were asked to design one – how might it look?

In the 1800s, the sky was the limit. Typewriter pioneers came up with all sorts of ingenious and imaginative ways to get letters onto the page.

Many experimental machines were built and used throughout the 19th century, but the heyday of typewriter invention and production came during the 1880s and 1890s. As the typewriter gradually gained acceptance and then became essential to the fast-growing business world, over 500 different designs were patented and more than 300 of them manufactured.

Among them were machines with curved keyboards, double keyboards – and even some with no keyboard at all. There were many notable successes, and just as many fascinating failures.

novelty to necessity

The Sholes and Glidden typewriter (1874) was initially marketed as a specialized tool for professionals such as lawyers, judges, stenographers, ministers, and editors. The first advertisement for the machine only mentioned at the end that “All men of business can perform the labor of letter writing with much saving of valuable time.”

As the typewriter proved itself indispensable in the office, demand grew rapidly across all sectors that relied on written records. Organizations sought the machine for its speed, legibility, and ability to create multiple copies (manifolding). By the mid-1880s, typewriters were in widespread use in offices, military services, medical institutions, churches, publishers, schools, and courts. Writers and journalists also embraced the advantages of switching from pen and ink.

Government agencies were seen as a promising market, but with rigid protocols for written communication, the U.S. government was slow to adopt the new technology. As late as 1897, The Typewriter World magazine lamented, “The records of State legislators and of Congress are scrawled on paper with a pen, just as they have been since 1777, when the first Congress assembled at Baltimore.”

As business rapidly expanded, the growing demands placed on office staff made managers increasingly open to labor-saving innovations, and old etiquette began to give way. The typewriter’s remarkable advantages – speed, legibility, and the ability to produce multiple copies – were impossible to ignore.

One early drawback, when the Sholes & Glidden typewriter was introduced, was the lack of trained typists. This began to change with the establishment of the first typing school at the YWCA in New York City in 1881. Many more schools quickly followed across the country. By 1886, just five years after demand began to rise, nearly every sizable office employed at least one typist. The typewriter was no longer a novelty – it had become a necessity.

Great Innovations

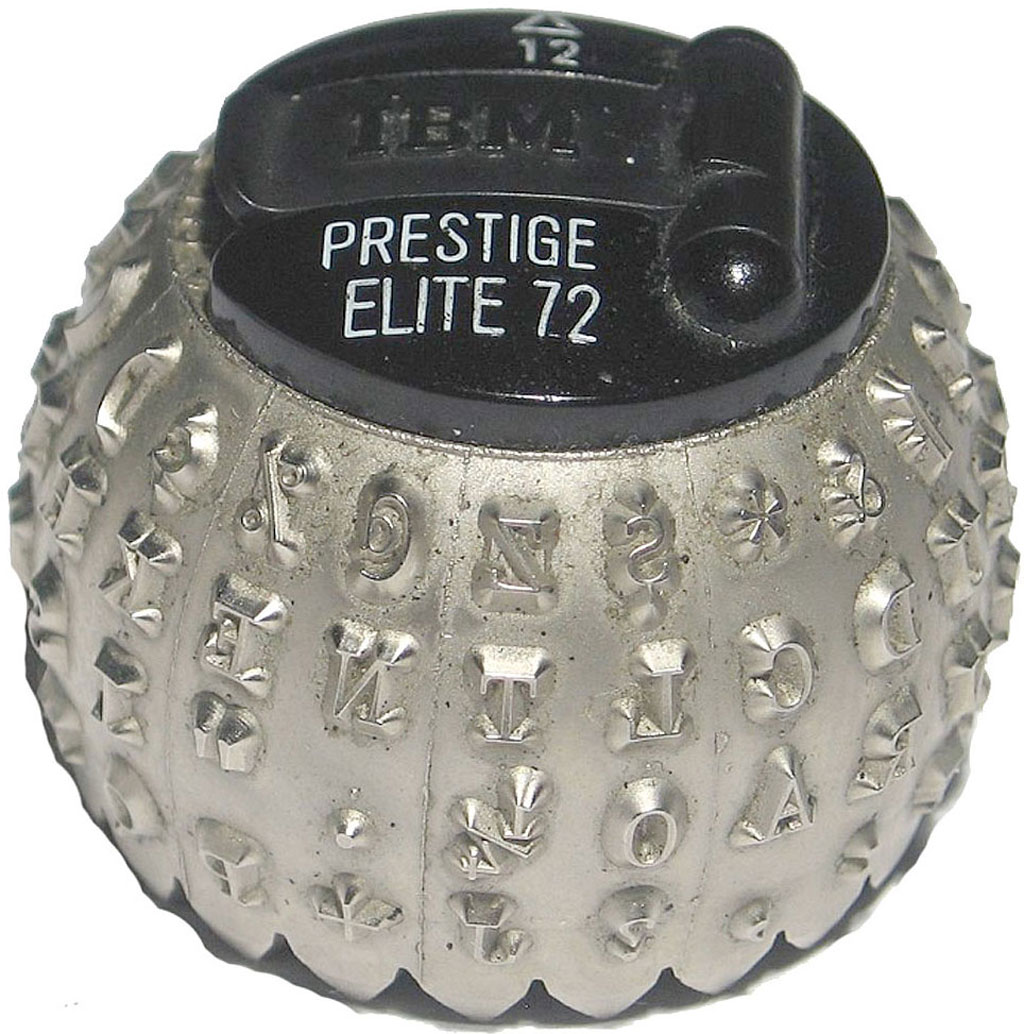

A single type element is a typewriter component that contains all the characters of the keyboard embossed on its surface. These elements came in various shapes – most notably cylinders and spheres. The IBM Selectric typewriter of 1961 uses a spherical element affectionately known as the “golf ball.”

Unlike conventional typewriters, which use individual typebars for each character, machines with a single type element have just one moving part for all characters. This offers several advantages, including consistent character alignment on the page and the ability to change fonts by swapping one type element for another.

The idea originated in the 19th century and was used in several remarkable machines, including the Hammond, Blickensderfer, and Munson. The very first manufactured typewriter to use a single type element was the Crandall 1 of 1883 (seen to the left). Its type element is a small cylinder, about the size of a finger, that rotates and rises into position to strike the correct character – much like the IBM golf ball.

Although the single type element fell out of use after the Underwood’s rise in 1896, it returned triumphantly with the IBM Selectric. That electric typewriter became the office standard for two decades and earned its own legendary status.

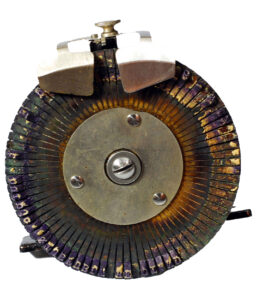

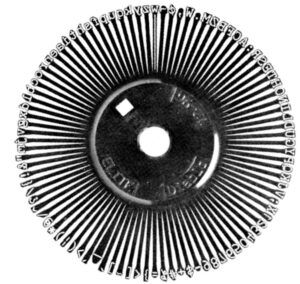

A type element is a single component that contains all the characters of the keyboard embossed on its surface. One form of this is the daisy wheel – so named because it resembles a small bicycle wheel, with a spoke for each character. At the end of each spoke is a molded character that strikes the paper.

Many electric typewriters and early computer printers of the 1970s and ’80s used daisy wheels, but the concept actually dates back to the 19th century. The first known use was in the Victor typewriter of 1889. The Victor’s daisy wheel had brass fingers radiating from a central hub – again, like spokes on a bicycle – with hardened rubber characters at their tips. When a character was selected using the swinging lever, the wheel rotated into position, and pressing a key caused a rod to push the chosen spoke, printing the character.

Although the daisy wheel appeared on only a few 19th-century machines – such as the Edland, also featured in this collection – this inventive approach to typing would not find widespread success until nearly a century later.

The Beginning of standardization

The Sholes & Glidden typewriter (Remington 1) saw a slow start when it launched in 1874, but sales gradually picked up. Still, its limitations – typing only in uppercase and requiring frequent adjustments to maintain alignment – restricted its broader success.

In 1878, the Remington 2 was introduced. It featured both upper and lowercase characters and proved far more reliable. By this time, typewriters were steadily entering business offices as the world began catching up with this revolutionary invention.

The Remington 2 used what is called a blind-writing design: the typebars struck the underside of the platen, so to see what you had typed, you had to pause and lift the carriage. Yet, despite this inconvenience, the company’s motto optimistically proclaimed, “To Save Time is to Lengthen Life.” The Remington 2 became a bestseller and would go on to be the “Model T” of typewriters well into the early 20th century.

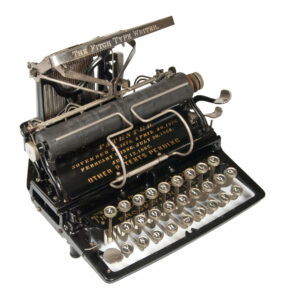

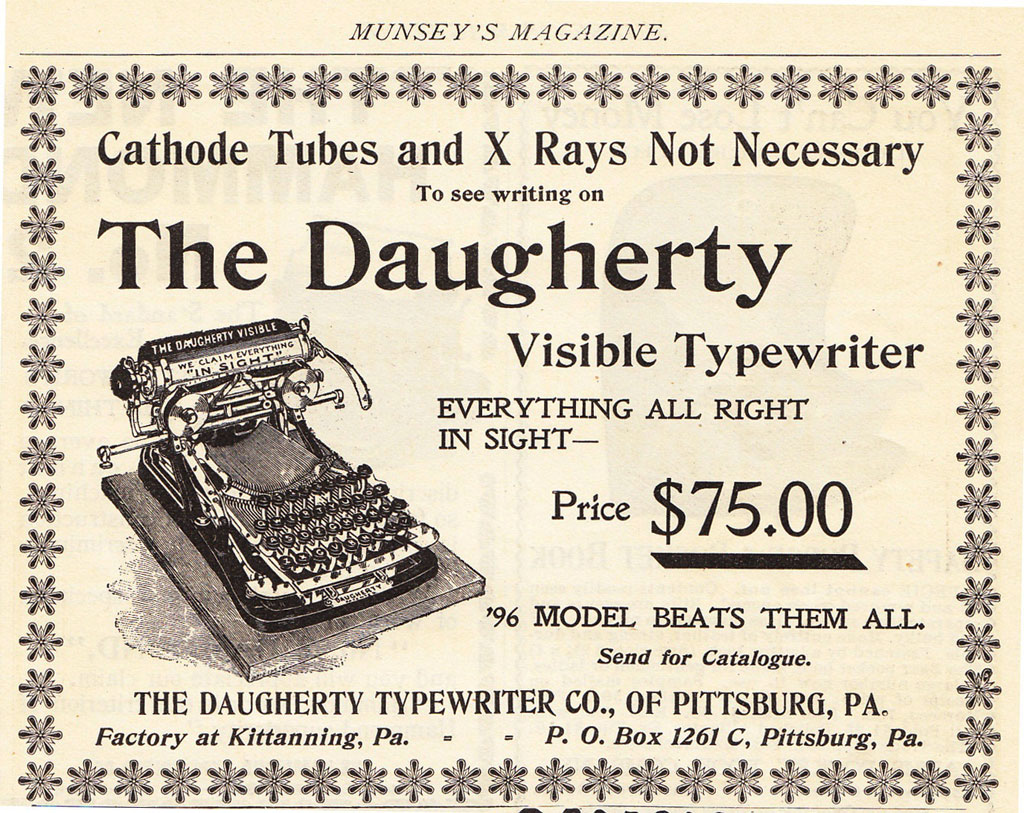

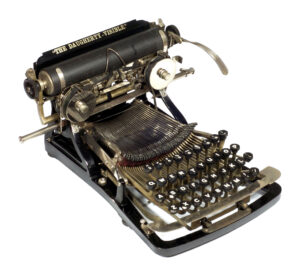

The Daugherty typewriter of 1893 was the first manufactured machine to feature the three essential design elements that would define the 20th-century typewriter: four rows of straight keys, a single shift key, and type bars that strike the front of the platen – offering visible typing.

Despite its winning layout, the Daugherty wasn’t a fast machine. The key levers were long and somewhat wobbly, limiting typing speed. Still, the configuration – with the typebars arranged in a semi-circle behind the keyboard and in front of the carriage – was a breakthrough. It’s remarkable that this intuitive layout had eluded so many inventive typewriter pioneers. Other machines, such as the Franklin, also used a semi-circular typebar arrangement, but failed to place the bars in this ideal forward position.

While the Daugherty saw only modest success, it had answered the crucial question of where to place the typebars. Just a few years later, in 1896, Franz Wagner would introduce the milestone Underwood typewriter – borrowing the Daugherty’s configuration. But unlike the Daugherty, the Underwood was fast, responsive, and ready for the modern office. It quickly became the new standard.

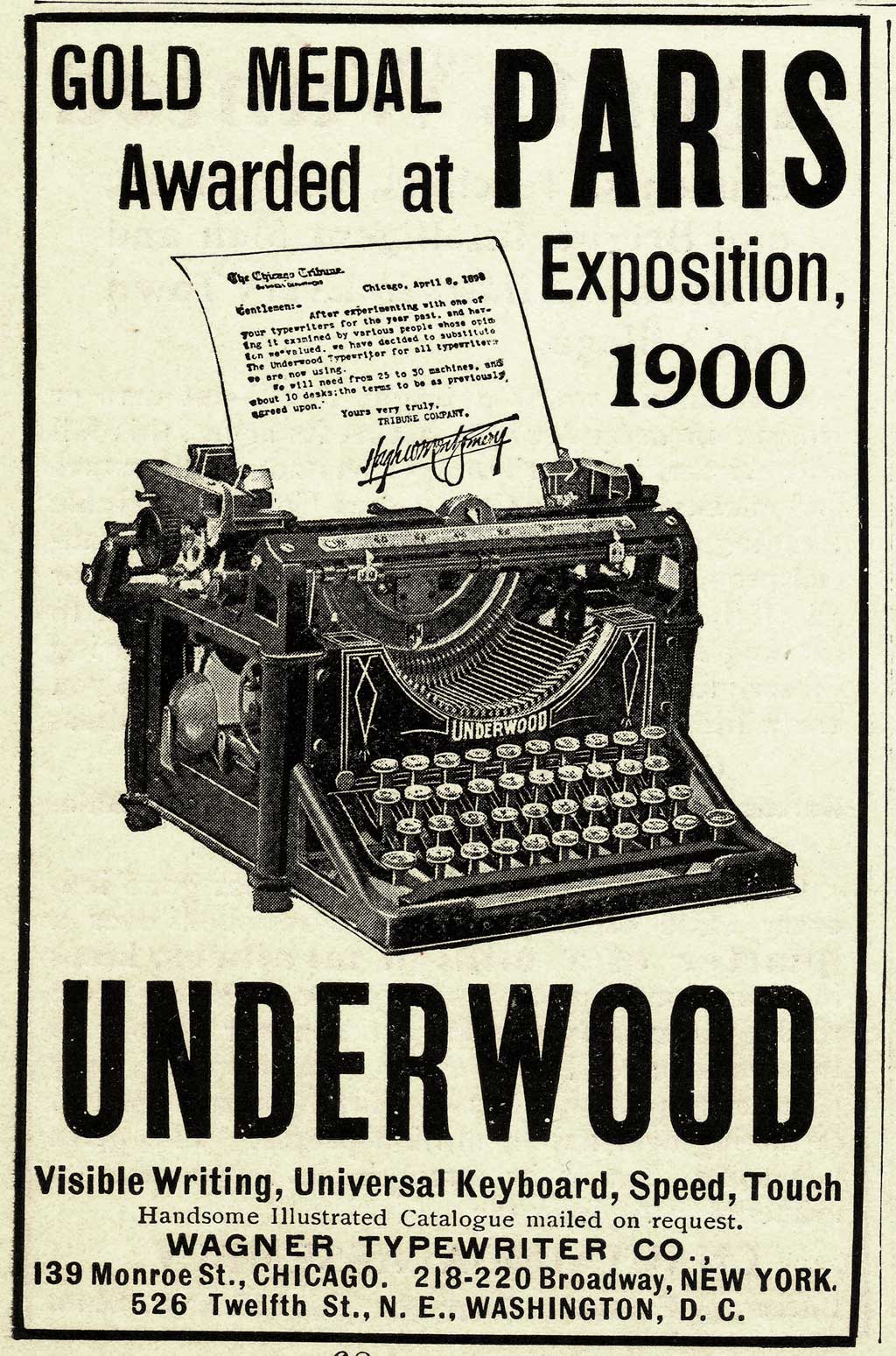

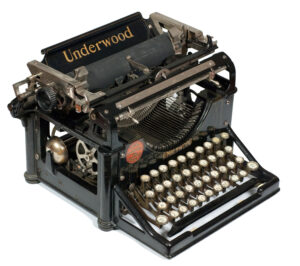

The Underwood typewriter was invented by Franz Wagner, a brilliant engineer who had earlier designed the Caligraph (1880). When the Underwood appeared in 1896, it quickly set the standard for the next century. It featured the key design elements that defined modern typewriters: four rows of straight keys, a single shift key, and typebars that struck the front of the platen, allowing for visible typing.

What truly set the Underwood apart, though, was its light and fast touch – it was simply superb to type on.

Within just a few years, the Underwood ushered in the new century and brought an end to the rich diversity of typewriter experimentation that had defined the previous decades.