Despite its name, the Edison Mimeograph Typewriter was invented by Albert B. Dick and manufactured and sold by the A. B. Dick Company. To understand this attribution, one must look back to the developments that led to the invention of this intriguing and ultimately ill-fated typewriter.

Thomas Edison received a patent in 1876 for ‘Autographic Printing,’ which covered the electric pen and a flatbed press. A related patent for ‘Autographic Stencils’ followed in 1880. These stencils were treated wax paper sheets that were perforated by his electric pen to create a master copy for duplicating handwritten documents or drawings.

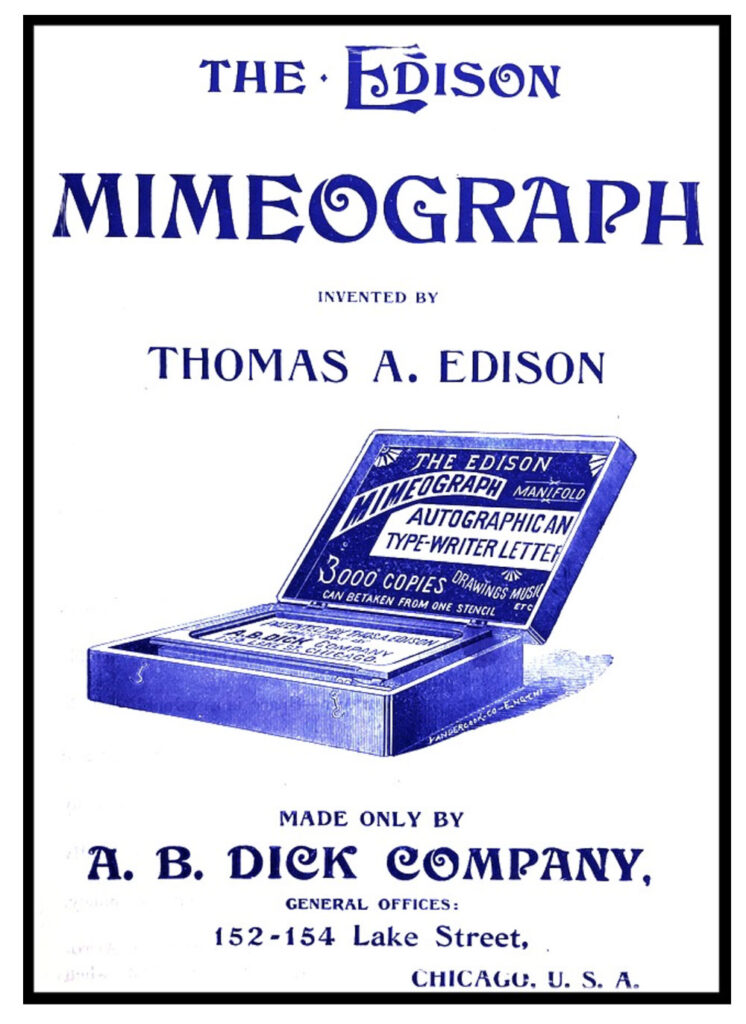

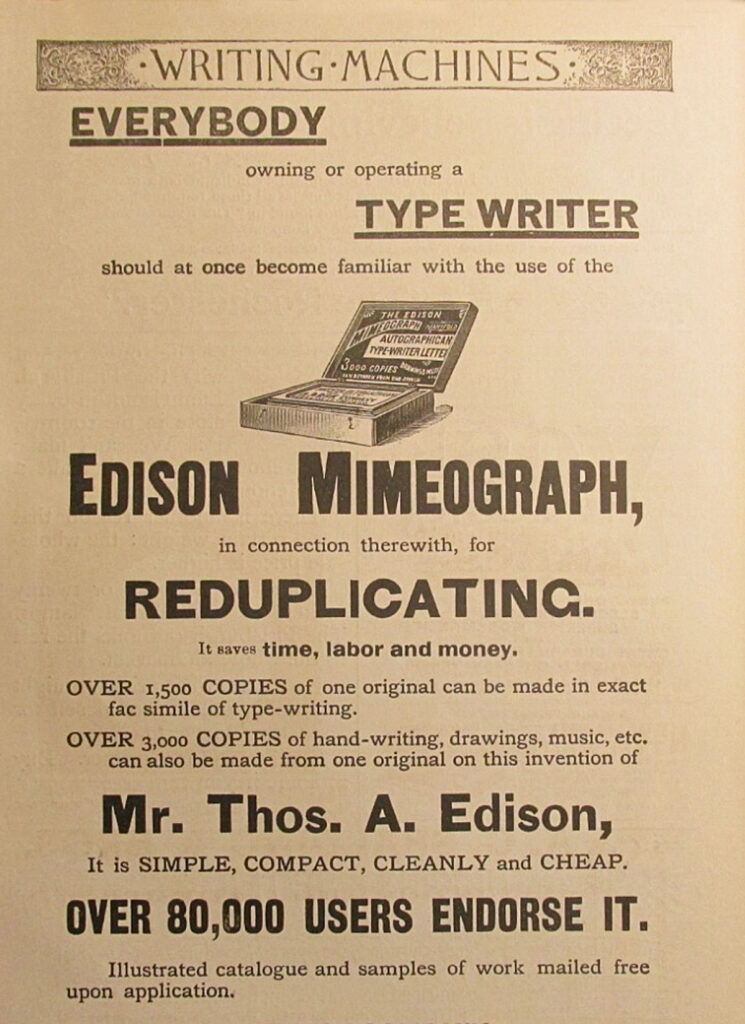

Dick licensed and refined Edison’s patents in 1877 and created the Mimeograph, from mimēma meaning something imitated and graph meaning to write. The following year he purchased a patent for a wax-coated stencil backed by porous tissue, that would not tear, for use on his Mimeograph.

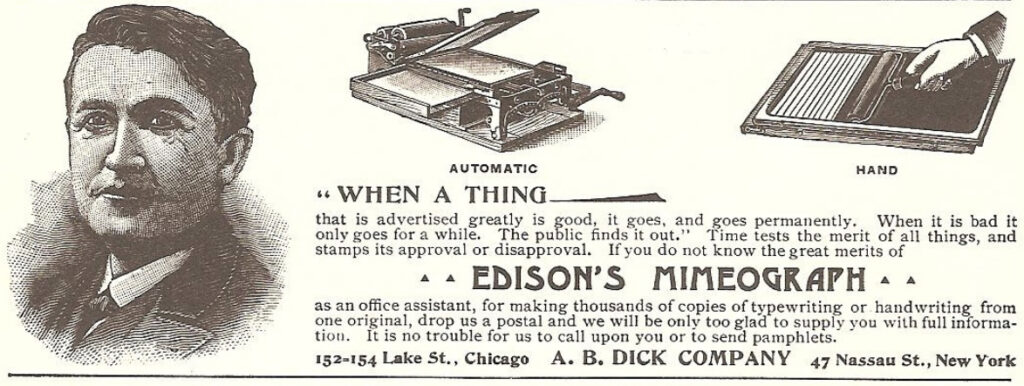

For marketing purposes, Dick astutely branded the device the Edison Mimeograph, even going so far as to state that Edison himself had invented it, a claim prominently featured in contemporary advertising. This inexpensive, stencil-based printing technology proved enormously successful and remained in widespread use until it was displaced by photocopying in the 1960s.

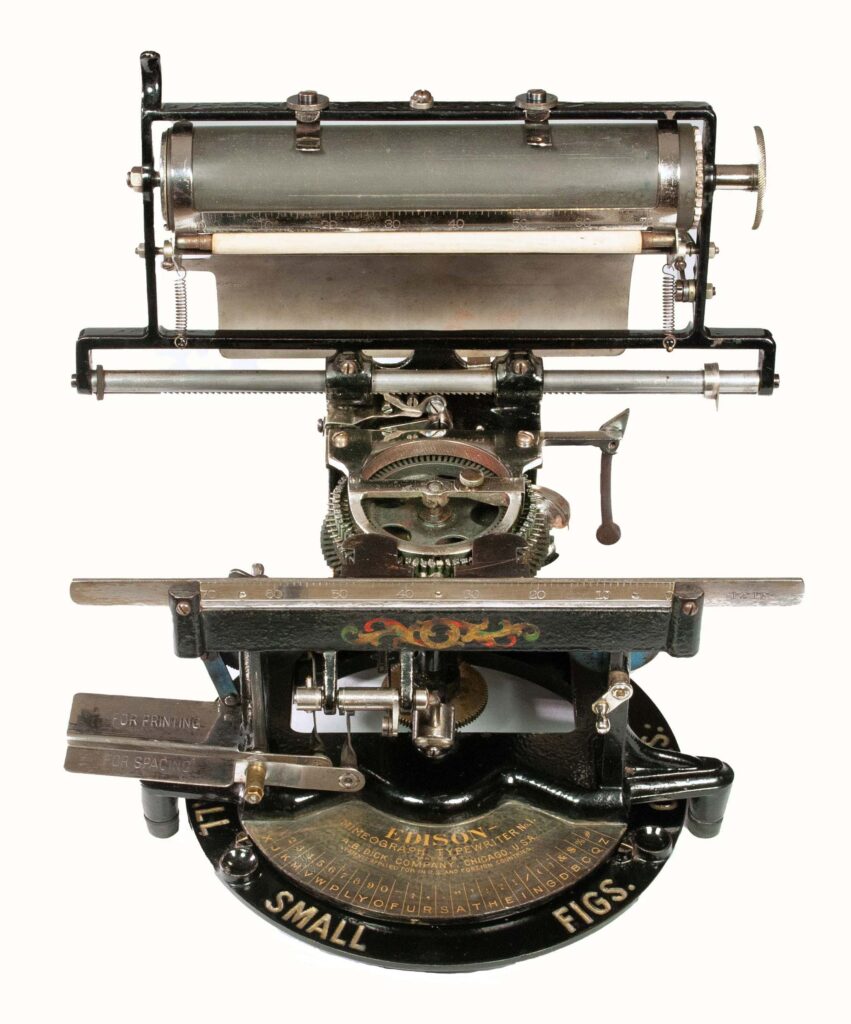

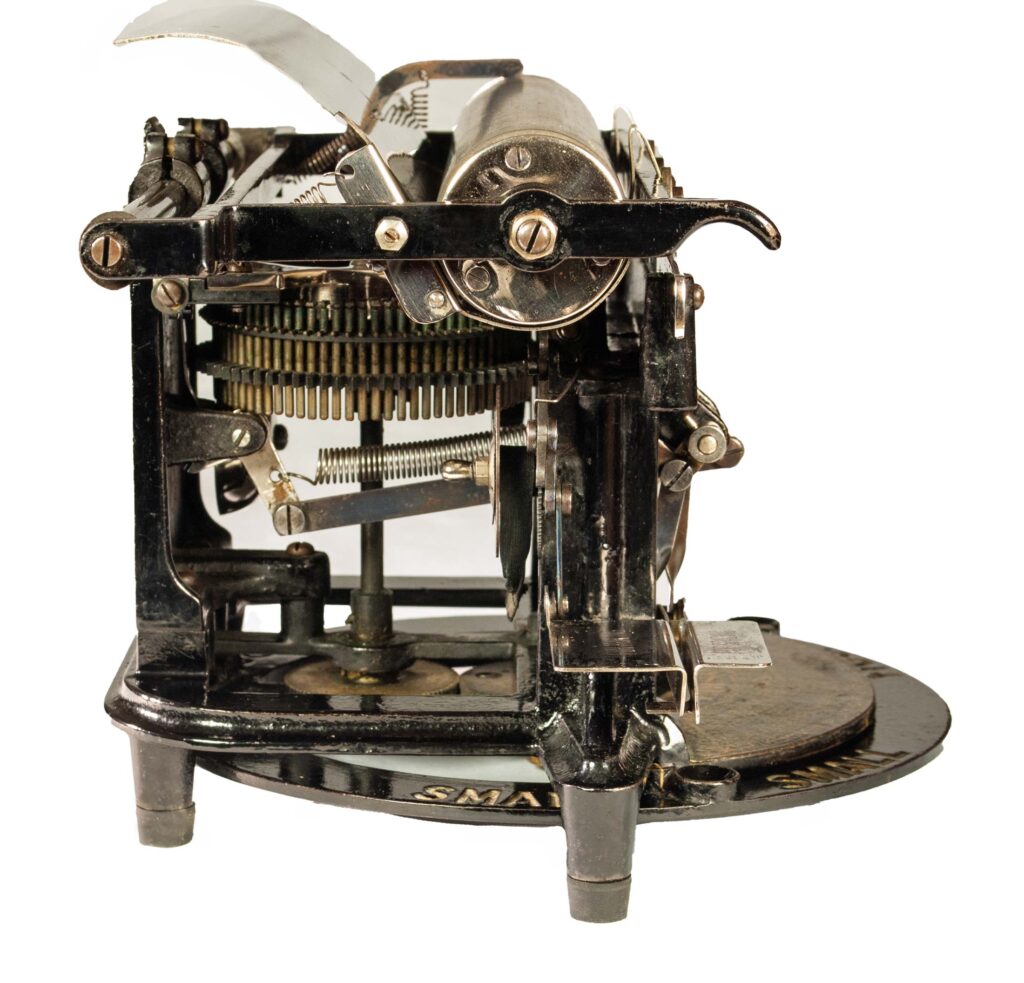

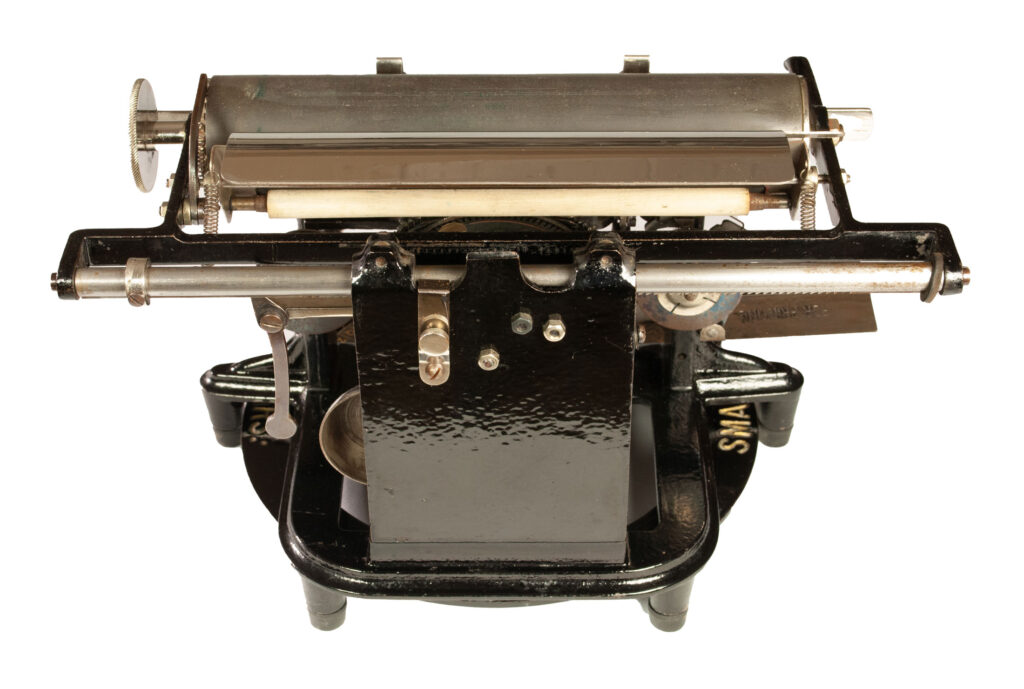

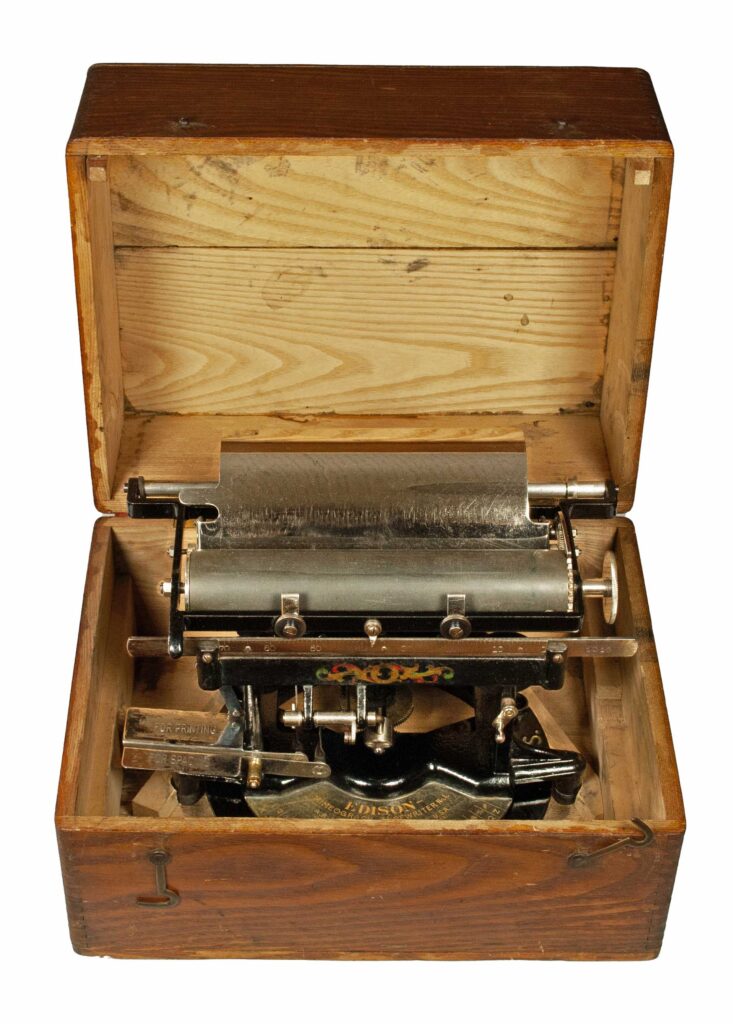

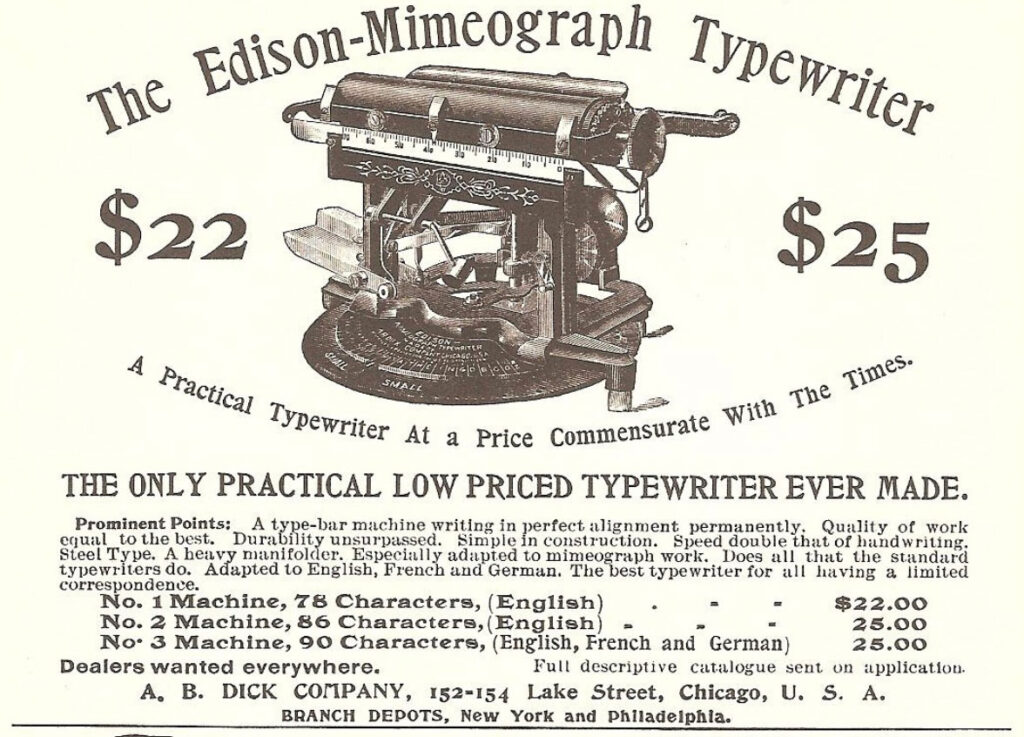

Buoyed by the success of the Mimeograph, Dick turned his attention to designing a typewriter that would exploit his improved stencil technology. With these stencils, a typewriter’s typebars could penetrate the wax coating without tearing the stencil itself, making it possible to create multiple copies from typed originals using a mimeograph, rotary printer, or printing press. The resulting machine, the Edison Mimeograph Typewriter, was designed primarily to prepare stencils for Mimeograph duplication, although it was optimistically marketed as suitable for general typing as well. Once again, Edison’s name was applied to the machine for its considerable marketing value.

Despite being well advertised and with the Edison name attached, the typewriter was a commercial failure and was withdrawn from the market within two years. The reasons were twofold. First, the machine was awkward to operate and slow in comparison with contemporary typewriters. Second, Dick’s improved wax stencils could be used effectively on many full-keyboard typewriters, which were faster, more versatile, and already well established.

As an artifact, the Edison Mimeograph Typewriter occupies a place in the history of duplicating technology, with its failure helping to illuminate the challenges inventors faced in developing new technologies. As a collectible early typewriter, it remains a striking, elegant, and intriguing machine.